Index

How to cite

Lee, Frederick and Lee, Angela (2024) ‘Water Resources in Hong Kong, in Lee, Frederick. (ed) Water Resources Information Portal. Hong Kong: Centre for Water Technology and Policy, The University of Hong Kong.

Rainfall in Hong Kong

1.2 Will Hong Kong get more rain or less rain in the future?

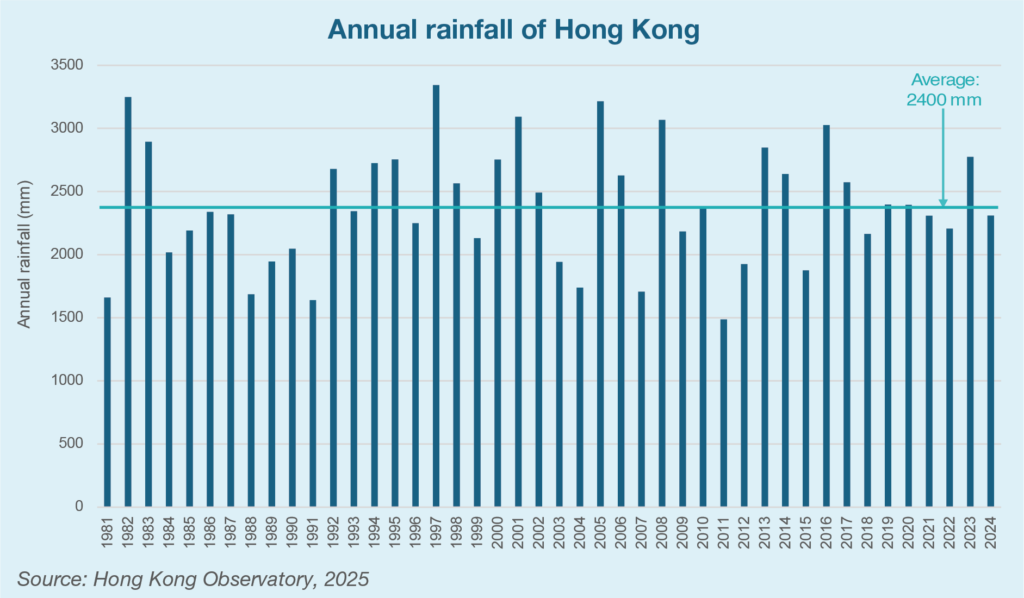

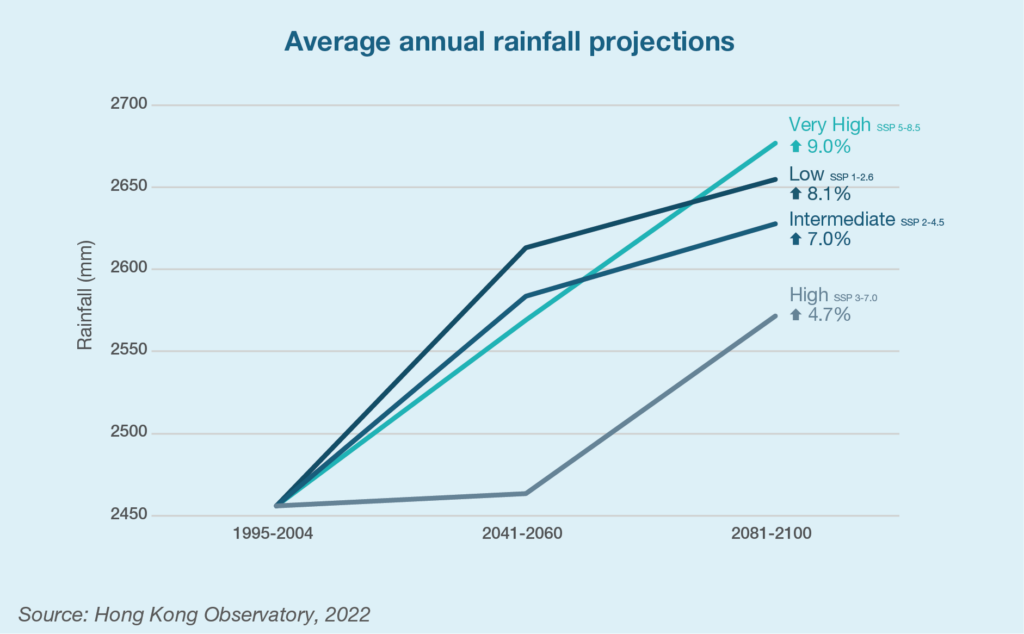

According to the Hong Kong Observatory, there is a projected increase in rainfall for the period of 2081-2100, compared to the 1995-2004 average annual rainfall figure of 2,456 mm.

Based on an analysis of scenario data provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, calculations suggest a 4.7% increase under the high emission scenario (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, SSP 3-7.0), and a 9.0% upswing under the very high emission scenario (SSP 5-8.5).

1.3 What is local yield?

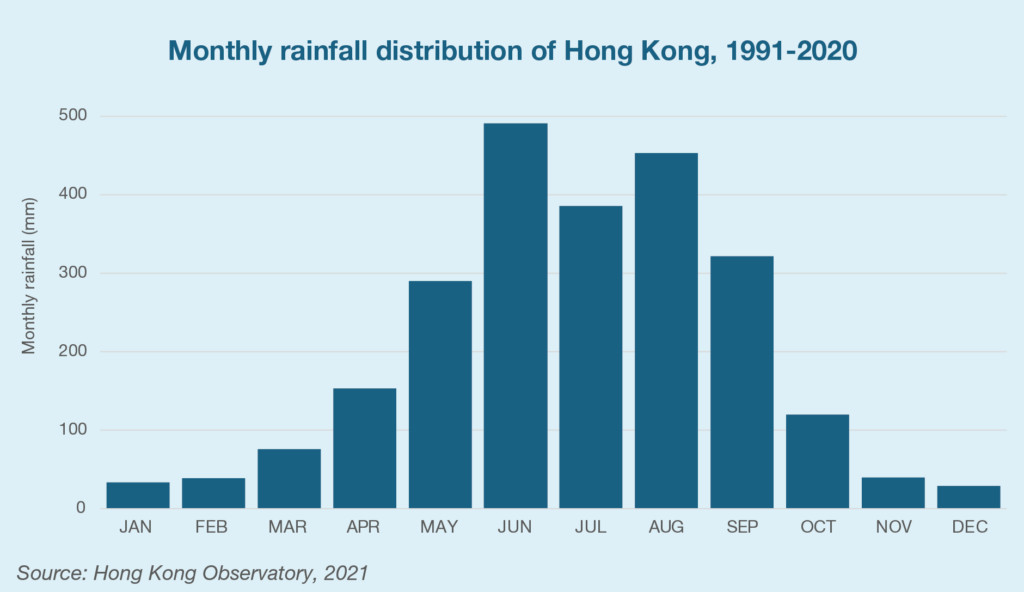

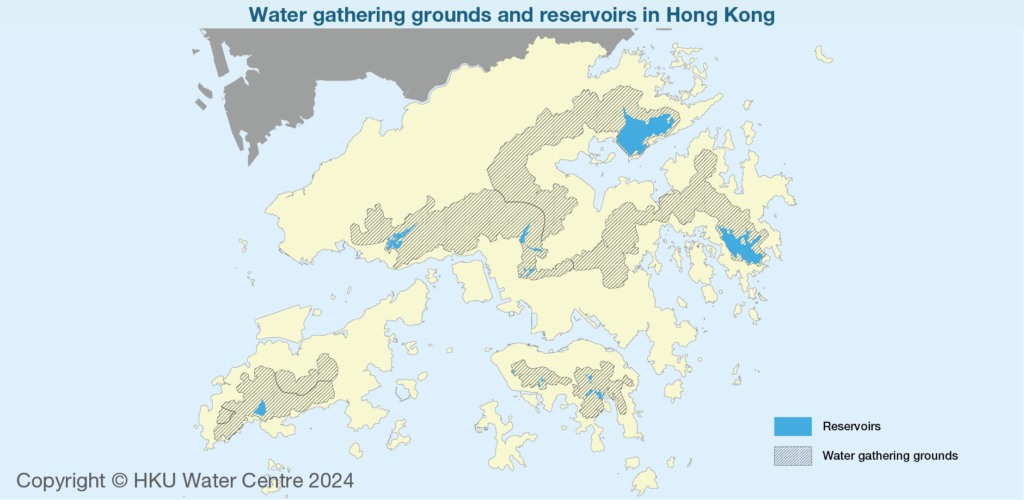

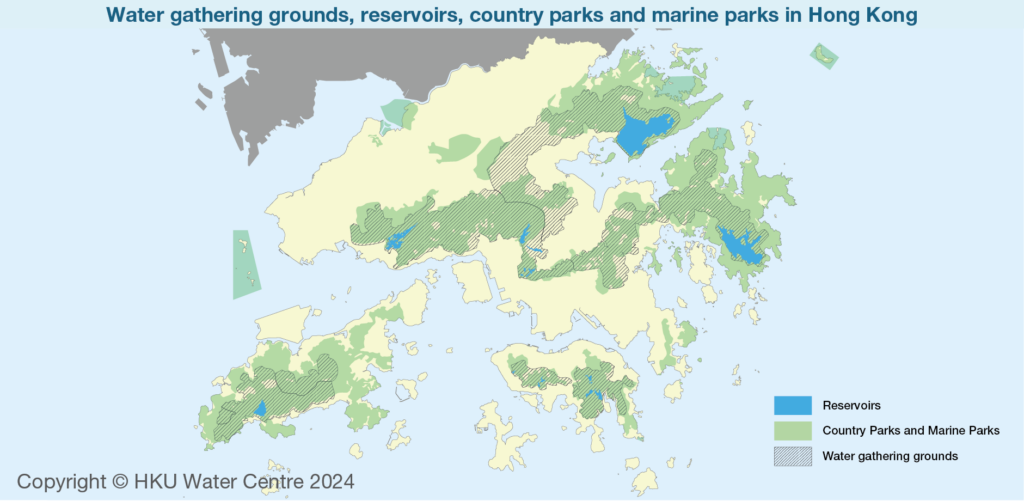

Local yield refers to rainwater that is captured by water gathering grounds.

Water gathering grounds

Rivers

1.8 Where can we find natural rivers in Hong Kong?

1.9 What is a river landscape?

1.10 In what ways does flowing water shape river channels?

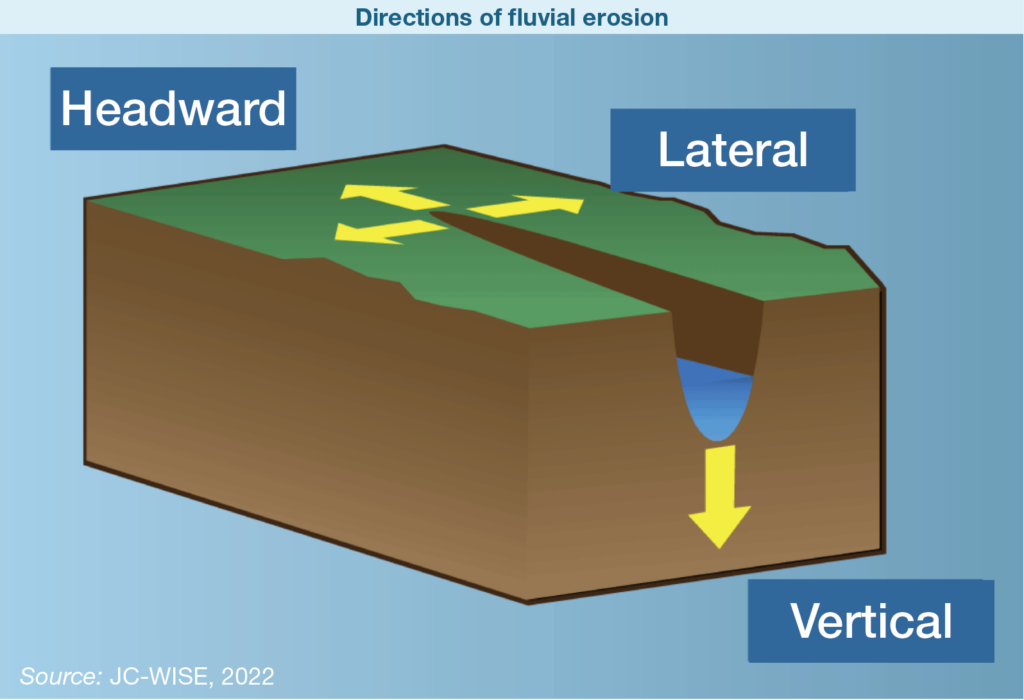

Moving water shapes the land surface by fluvial erosion and creates a network of channels. Fluvial erosion occurs in three directions:

- Headward erosion: River erodes in an upstream direction, lengthening the river channel.

- Lateral erosion: River erodes laterally, widening the river channel.

- Vertical erosion: River erodes downwards, deepening the river channel.

There are four types of fluvial erosion:

- Hydraulic action: The shearing force of the water hits the river banks, causing rocks and sediments to crack and break apart.

- Abrasion: Materials carried by the river wear away river banks and bed.

- Attrition: Rocks carried by the river collide with each other and are broken into smaller and rounder rock particles.

- Solution: Soluble parts of rocks and sediments are dissolved in the river.

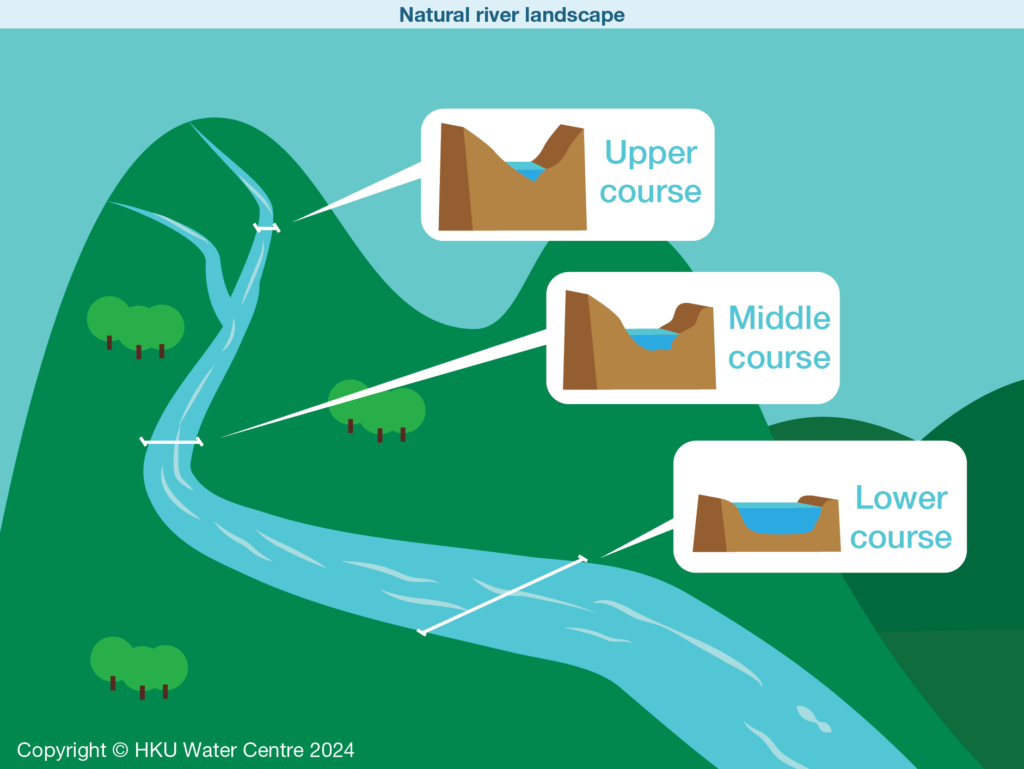

1.11 What are the key characteristics of the major sections of a river?

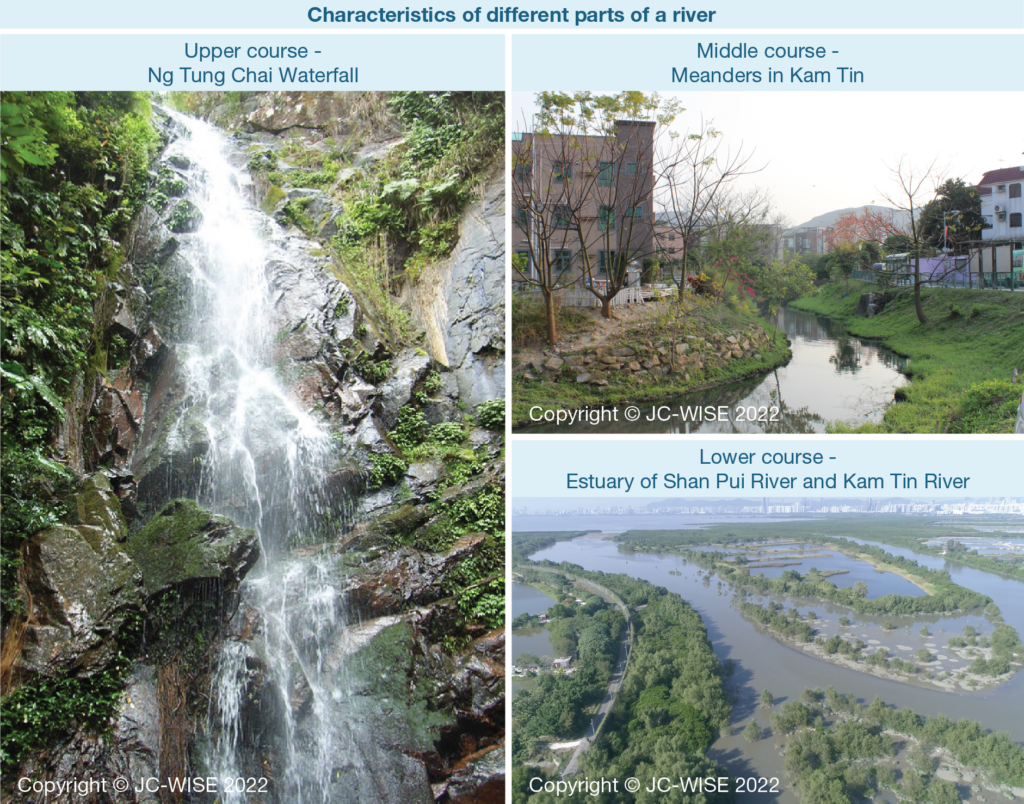

The upper course of a river is usually located uphill, featuring a steep gradient and a small river discharge. Major landforms include interlocking spurs, plunge pools, and waterfalls.

The middle course has a gentle gradient and a medium discharge level, with major landforms including meanders.

The lower course is characterised by a very gentle slope and a large discharge, with a major landform being the floodplain.

For more details, please click here.

1.12 What are the key characteristics of natural rivers in Hong Kong?

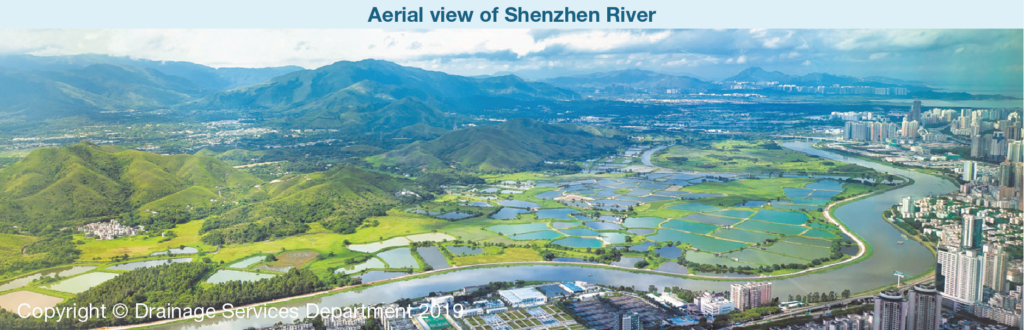

In Hong Kong, rivers are typically short and lack a middle course. Most natural rivers in Hong Kong are not “perennial streams” that flow throughout the year. Instead, many are “intermittent streams”, flowing only during the wet season, or “ephemeral streams”, responding to rainfall.

1.13 Why is it important for us to protect natural rivers?

Rivers and streams play a crucial ecological role and serve as vital habitats for diverse plant and animal life. In Hong Kong, rivers are home to over 190 species of freshwater fish and 20 species of frogs.

Recognising their high ecological value, the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department has designated 33 natural streams and rivers as Ecologically Important Streams.

Preserving these habitats is essential to maintaining biodiversity health.

For more details, please click here.

1.14 Are all the rivers in Hong Kong natural rivers?

No, not all rivers in Hong Kong are natural.

Some natural river channels, originating from or passing through urban areas, have been significantly altered and transformed into concrete-lined drainage ditches.

These extensively modified drainage channels are referred to as urban channels (or urban rivers) and were known as “nullahs” in the past.

1.15 How are rivers associated with reservoirs?

The streamflow of some rivers is intercepted by man-made water intake points. The intercepted water is then diverted to reservoirs via catchwaters.

Reservoirs

1.18 What major categories of reservoirs do we have in Hong Kong?

There are two major categories: Impounding reservoirs and irrigation reservoirs.

| Impounding reservoirs | Capacity (mcm) | |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | High Island Reservoir | 281.124 |

| 02 | Plover Cove Reservoir | 229.729 |

| 03 | Shek Pik Reservoir | 24.461 |

| 04 | Tai Lam Chung Reservoir | 20.490 |

| 05 | Shing Mun Reservoir | 13.279 |

| 06 | Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir | 6.047 |

| 07 | Lower Shing Mun Reservoir | 4.299 |

| 08 | Kowloon Reservoir | 1.578 |

| 09 | Tai Tam Upper Reservoir | 1.490 |

| 10 | Kowloon Byewash Reservoir | 0.800 |

| 11 | Aberdeen Upper Reservoir | 0.733 |

| 12 | Tai Tam Intermediate Reservoir | 0.686 |

| 13 | Aberdeen Lower Reservoir | 0.486 |

| 14 | Shek Lei Pui Reservoir | 0.374 |

| 15 | Pok Fu Lam Reservoir | 0.233 |

| 16 | Kowloon Reception Reservoir | 0.121 |

| 17 | Tai Tam Byewash Reservoir | 0.080 |

| Irrigation reservoirs | |

|---|---|

| 01 | Hok Tau Irrigation Reserviors |

| 02 | Lau Shui Heung Irrigation Reservoir |

| 03 | Tsing Tam Upper Irrigation Reservoir |

| 04 | Tsing Tam Lower Irrigation Reservoir |

| 05 | Ho Pui Irrigation Reservoir |

| 06 | Wong Nai Tun Irrigation Reservoir |

| 07 | Hung Shui Hang Irrigation Reservoir |

| 08 | Lam Tei Irrigation Reservoir |

| 09 | Shap Long Irrigation Reservoir |

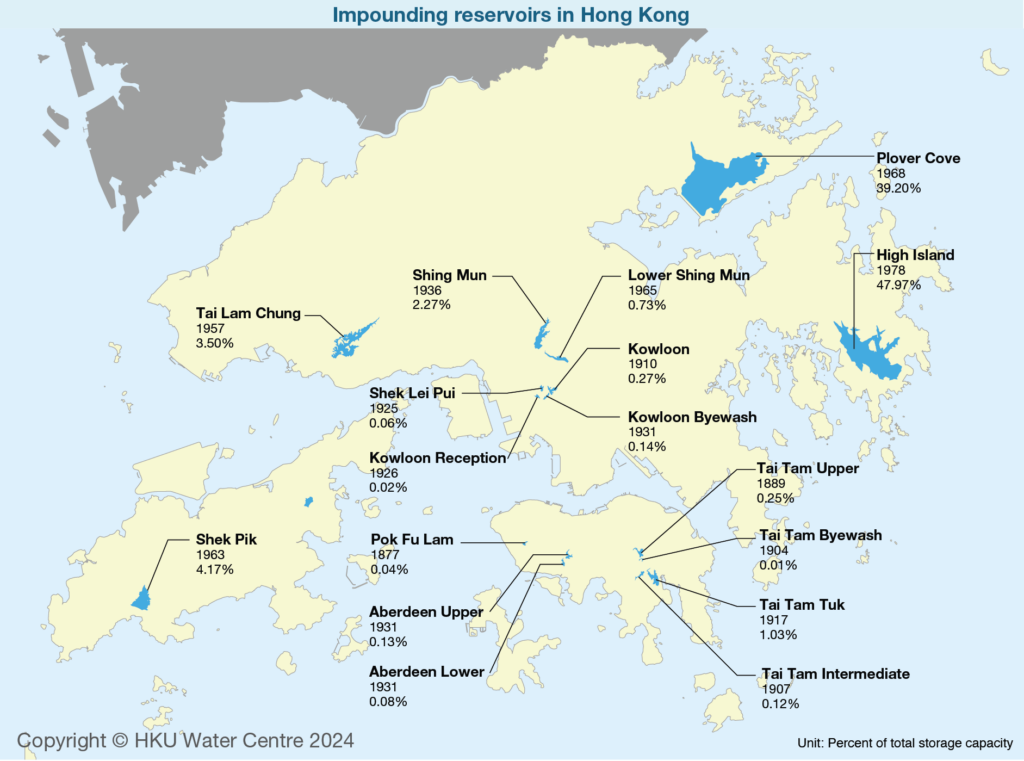

1.19 How many impounding reservoirs do we have in Hong Kong?

There are 17 in-use impounding reservoirs. In addition, there are one obsolete impounding reservoir (Wong Nai Chung Reservoir) and nine obsolete irrigation reservoirs.

1.20 What is the main function of Hong Kong’s impounding reservoirs?

Impounding reservoirs store rain water collected by water gathering grounds; some of them also store imported freshwater from Dongjiang.

1.21 What is the storage capacity of the impounding reservoirs in Hong Kong?

The overall storage capacity of the 17 impounding reservoirs in Hong Kong is 586.05 million cubic meters (mcm).

High Island Reservoir, the largest, has a storage capacity of 281 mcm, while Tai Tam Byewash Reservoir, the smallest, has a storage capacity of 0.08 mcm.

1.22 In what ways could local yield be augmented?

A majority of the reservoirs are located within a natural drainage basin. In addition to collecting rainwater from its natural basin, supplementary catchwaters have been constructed to divert rainwater from adjacent natural basins to the reservoirs, thereby increasing the amount of water entering the reservoirs. The catchment areas lying outside of the reservoir’s natural drainage basins are also known as “indirect catchment areas.”

For example, a nine-kilometer-long catchwater system was built to connect several basins outside of the catchment of Shing Mun Reservoir. This system connects several adjacent catchments—such as Ha Fa Hang, Sheung Fa Hang, Pak Shek Kiu Hang, Ngau Liu Hang, Tai Tso Stream, and Tai Yuen Stream—to Shing Mun Reservoir.

This supplementary catchwater system facilitates the capture of additional rain water to be stored in Shing Mun Reservoir, beyond the amount captured by its direct catchment area.

1.23 Why are irrigation reservoirs no longer in use?

Irrigation reservoirs are no longer operational because the demand for irrigation water has dropped precipitously since the 1970s. A significant decline in agricultural activities and a drastic reduction in the size of farmlands due to urban development have rendered the function of irrigation reservoirs obsolete.

1.24 Do we need to worry when we see a dried-up reservoir bed?

There is no need for concern if the dried-up reservoir bed belongs to reservoirs such as Lower Shing Mun Reservoir, Tai Tam Intermediate Reservoir, and Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir. These reservoirs serve a flood management purpose; they were built to hold excess water that overflows from higher-elevation reservoirs. It is normal for them to have lower water levels or be empty in the drier months.

In addition, irrigation reservoirs, such as Lau Shui Heung Reservoir, were originally designed to supply water for agricultural use, not potable use. Since they do not store water for potable use, there is no need for concern if they record lower water levels or are empty in the drier months.

2. Dongjiang (East River)

Introduction

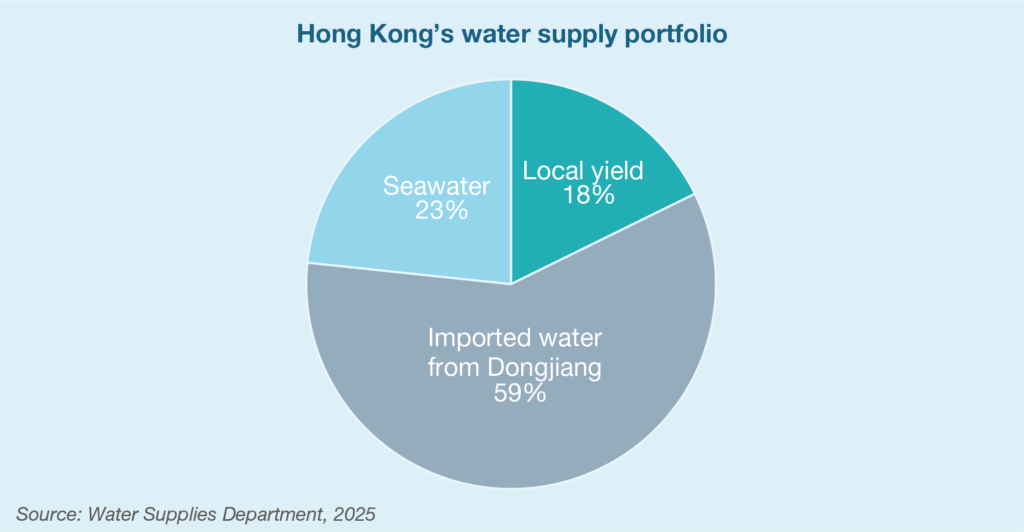

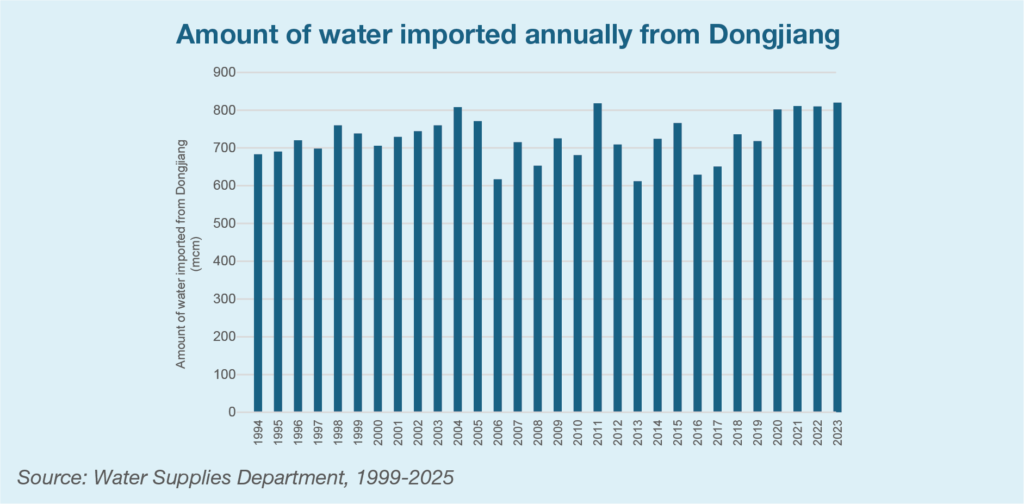

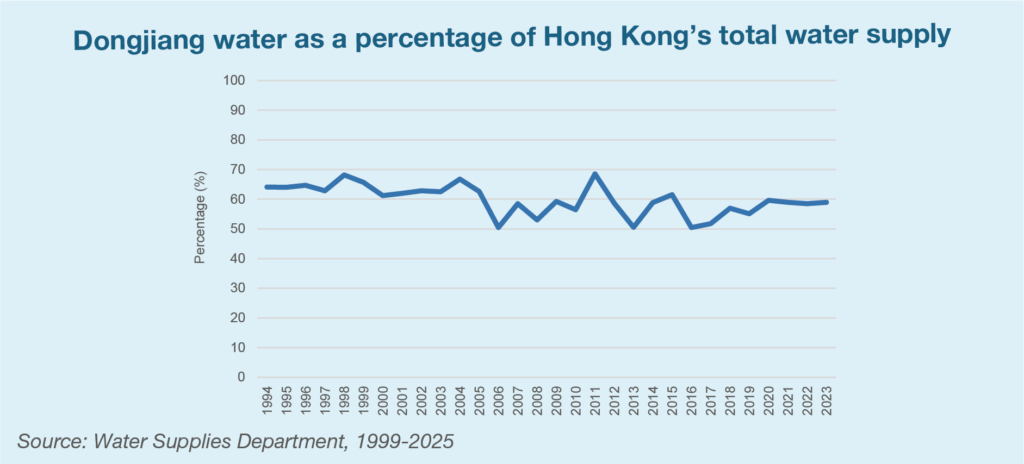

Population and economic growth in the post-war period outpaced the capacity of local water gathering grounds to meet Hong Kong’s growing water demand. Since 1965, Hong Kong has supplemented its locally captured freshwater by importing water from Dongjiang (East River). In 2023-24, water imported from Dongjiang constituted 59% of Hong Kong’s total water supply.

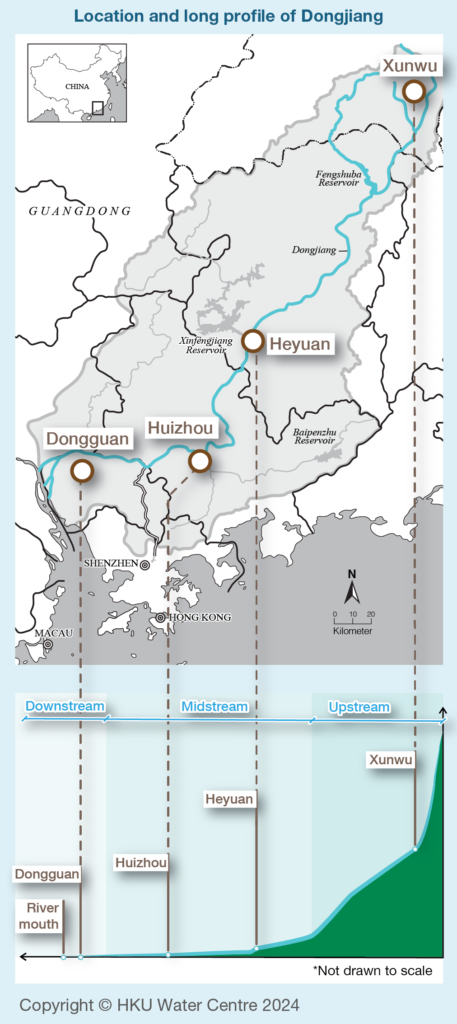

Dongjiang river basin

2.2 Why did Hong Kong need to import freshwater since the 1960s?

Hong Kong needed to import freshwater since the 1960s because local yield was not sufficient to meet growing water demand.

2.3 From which river has Hong Kong been importing freshwater?

Hong Kong has been importing freshwater from Dongjiang since 1965.

2.4 Which cities are located inside the Dongjiang river basin?

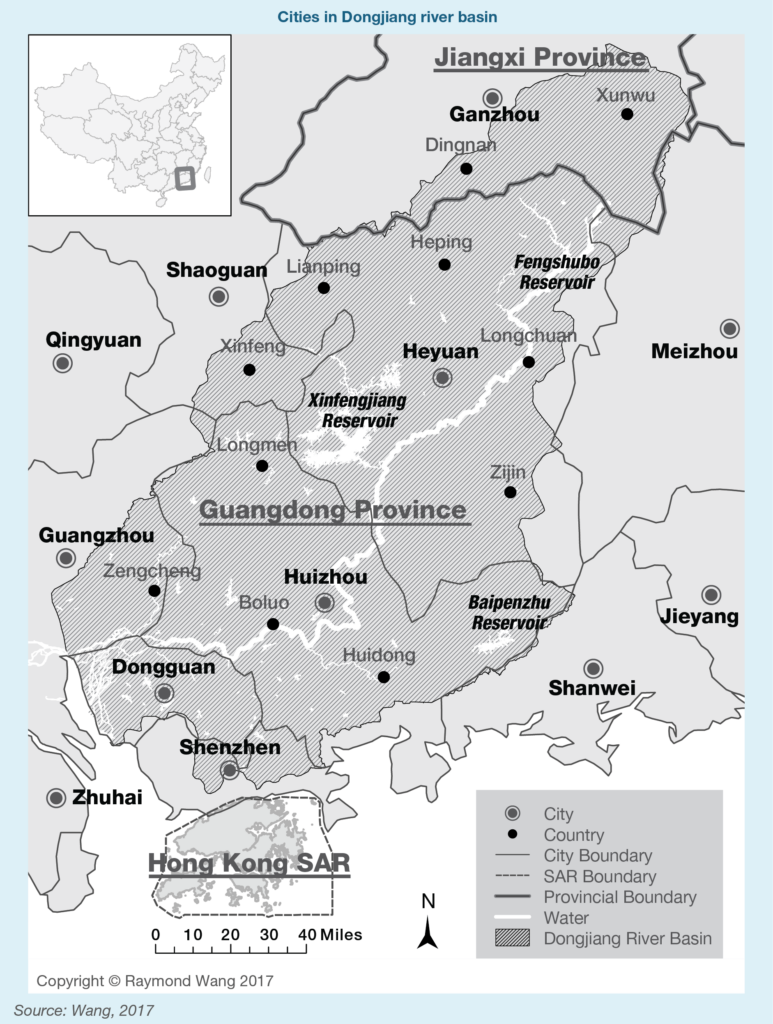

In the upstream zone: Ganzhou in Jiangxi Province, and the northern parts of Heyuan and Meizhou in Guangdong Province.

In the midstream zone: Heyuan, Shaoguan, and the northern and eastern parts of Huizhou in Guangdong Province.

In the downstream zone: Huizhou, Guangzhou, Dongguan and Shenzhen.

While Hong Kong lies outside of the Dongjiang river basin, it draws water from the downstream zone of Dongjiang through an inter-basin transfer scheme.

2.5 Which cities take in water from Dongjiang?

One upstream city (Meizhou), three midstream cities (Heyuan, Huizhou, and Shaoguan), three downstream cities (Dongguan, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen), and one city located outside the Dongjiang basin (Hong Kong) draw water from Dongjiang.

Dongjiang provides freshwater supply to more than 40 million people in these eight cities.

2.6 Is there a high probability of Hong Kong being exposed to the risk of water supply interruption in the drier years?

There is a very low probability that Hong Kong’s water supply would be interrupted in the drier years. The water abstraction ratio of Dongjiang is considered acceptable, with a 2021 reported long-term value of 27%.

The combined storage capacity of the three largest reservoirs in the Dongjiang river basin is sufficiently abundant to allow Guangdong’s water managers to perform one critical task: To control the release of water from these reservoirs, in times of drought, to ensure the river’s volumetric flow rate would reach a level that could satisfy downstream cities’ water demand.

Despite experiencing drier years, such as in 2021 when the rainfall amount in Dongjiang was 17.1% lowered than that of the previous year, Hong Kong’s freshwater supply has remained unaffected.

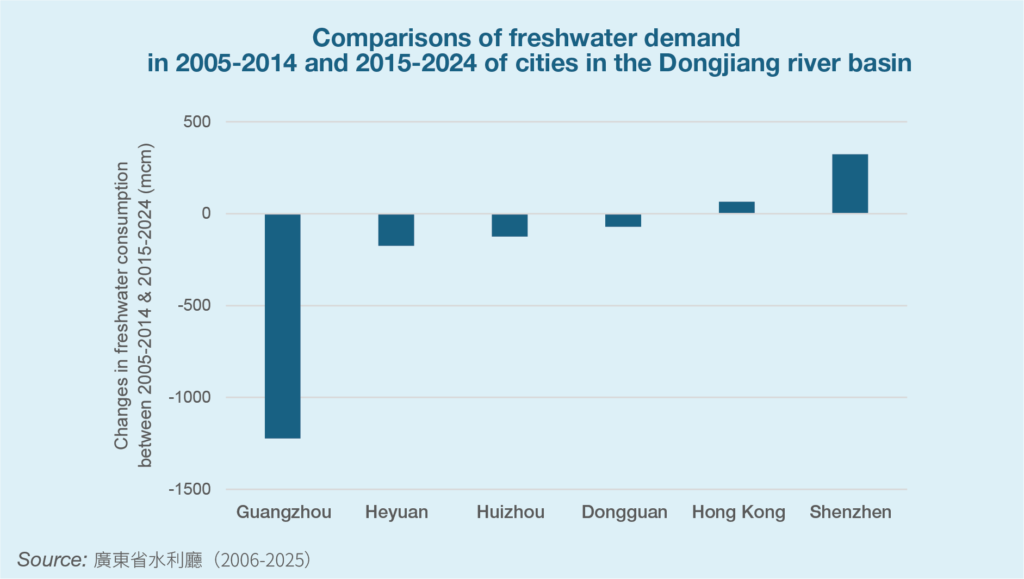

2.7 Are there any increased levels of competition for freshwater among cities drawing water from the Dongjiang?

No, there are no increasing levels of competition for water among Dongjiang basin cities because the overall demand for freshwater in the basin has already peaked in 2011. The peaking is attributed to a reduction in water demand caused by diminishing agricultural activities in Guangzhou and Heyuan, as well as a drop in industrial activities across most cities in the river basin. The increase in freshwater demand due to population growth has been offset by a reduction in freshwater consumption that results from economic restructuring.

Dongshen Water Supply System

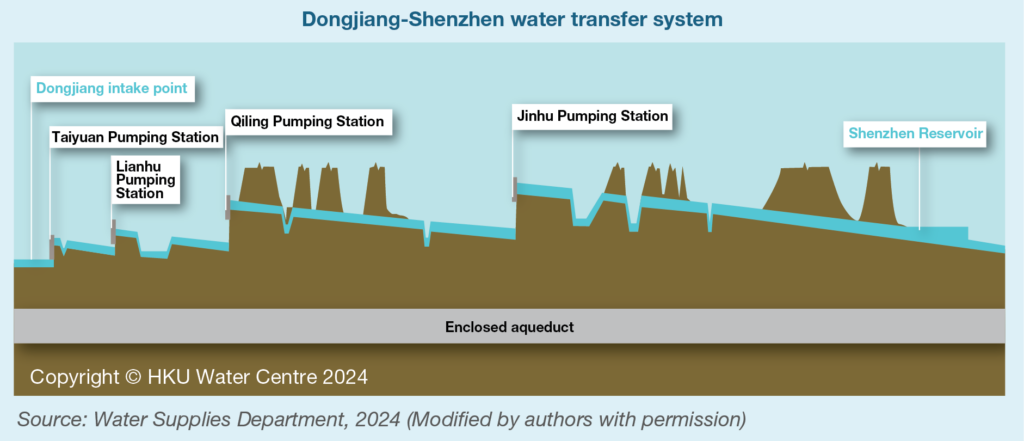

2.8 How is Dongjiang water conveyed to Hong Kong?

Rainfall collected by water gathering grounds in the Dongjiang river basin converges into the river’s main stem and flows along it towards the estuary.

Upon abstraction from a water intake point located in Dongguang, Dongjiang water is pumped uphill through four pumping stations (Taiyuan, Lianhu, Qiling, and Jinhu) to reach Shenzhen Reservoir.

The water is then conveyed by a pipeline to cross the border to reach the Muk Wu Pumping Station in Hong Kong.

Much energy is used to operate the transfer system’s pumping stations to enable Dongjiang water to reach Hong Kong.

2.9 Where does imported Dongjiang water go to after it is shipped into Hong Kong?

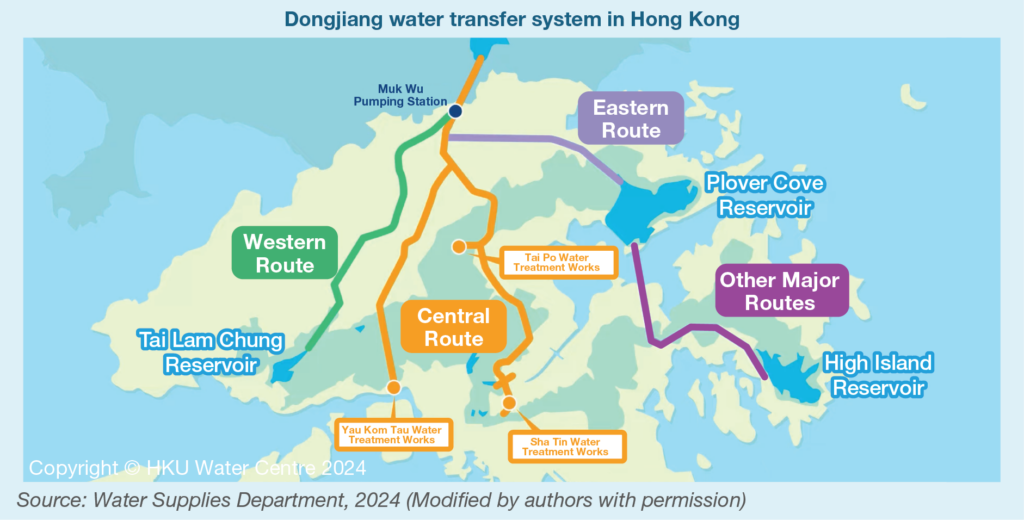

After reaching Muk Wu Pumping Station in Hong Kong, Dongjiang water is conveyed to three reservoirs, or is shipped directly to water treatment works.

On the Eastern Route, Dongjiang water is shipped to Plover Cove Reservoir and High Island Reservoir for storage.

On the Central Route, water is shipped to Yau Kom Tau Water Treatment Works, Tai Po Water Treatment Works and Sha Tin Water Treatment Works for treatment.

On the Western Route, water is either shipped to Ngau Tam Mei Water Treatment Works and Au Tau Water Treatment Works for treatment or conveyed to Tai Lam Chung Reservoir for storage.

2.10 Which reservoirs store imported Dongjiang water?

Three reservoirs—High Island Reservoir, Plover Cove Reservoir and Tai Lam Chung Reservoir—receive and store Dongjiang water.

2.11 To what extent should we be concerned about the quality of Dongjiang water?

Since 2003, a dedicated aqueduct has been utilised to convey Dongjiang water to Hong Kong to ensure its quality is kept up to specified standards.

The conveyance of Dongjiang water begins at Taiyuan Pumping Station. The water then flows to Shenzhen Reservoir via a dedicated aqueduct.

Imported water from Dongjiang undergoes treatment at water treatment plants in Hong Kong before it is supplied to users, complying with the city’s potable water standards.

Hong Kong Water Supply Agreement

2.12 What is the amount of imported water specified in the Hong Kong water supply agreement?

As per the 2020 Hong Kong Water Supply Agreement with Guangdong Province, the annual guaranteed supply ceiling of water imported from Dongjiang is 820 million cubic meters.

According to the 2008 Dongjiang Water Allocation Plan, Hong Kong has been alloted a maximum of 1,100 million cubic meters of Dongjiang water and can request this amount if needed.

2.13 How much has Hong Kong been paying for Dongjiang water?

In 2023, the annual ceiling water price for 820 million cubic meters of Dongjiang water was $5,016.35 million. On average, the cost of raw Dongjiang water was $6.12 per cubic meter.

2.14 How would the purchased but unused Dongjiang water be handled?

The purchased but unused water will not be imported into Hong Kong from Dongjiang.

2.15 How does the rebate mechanism contained in the Water Supply Agreement work?

Since 2020, a rebate mechanism has been incorporated into the Water Supply Agreement with Guangdong.

In each year, Hong Kong would make an upfront payment for 820 million cubic meters of water. According to the terms of the rebate mechanism, Hong Kong would receive approximately $0.304 per for each cubic meter of un-claimed water.

For instance, by the end of 2022, only 810 million cubic meters were imported into Hong Kong from Dongjiang, leaving 10 million cubic meters unused. As such, the total rebate amount was equivalent to $3.04 million (calculated as $0.304 x 10,000,000). This amount was deducted from the 2023 payment, reducing the latter from $5,016.35 million to $5,013.31 million, which works out to be a 0.06% discount.

3. Is Hong Kong a water-scarce city?

Introduction

Water provision in Hong Kong: Current situation and future considerations

3.1 Is Hong Kong a water-scarce city?

In terms of volumetric availability of tap water supply, Hong Kong is not a water-scarce city. In fact, based on this criterion, Hong Kong is a water-abundant city.

According to the 2008 Dongjiang Water Allocation Plan, in drier years, Hong Kong could import up to 1,100 million cubic meters of water. When this figure is combined with the lower bound figures of local yield, the allocated quantity under the Dongjiang Water Allocation Plan would help ensure Hong Kong has an abundant (i.e., more than sufficient) supply of freshwater.

Moreover, the completion, in January 2024, of a water diversion project that conveys water from the Xijiang (West River) to the Dongjiang river basin has further augmented Hong Kong’s overall freshwater supply. This project allows for the diversion of up to 1.7 billion cubic meters of water annually from the Xijiang to meet the water demand of three cities located inside the Dongjiang river basin, such as Guangzhou, Dongguan and Shenzhen. Project proponents say that it includes a provision of emergency supply of water to Hong Kong.

3.2 Is there a chance that Hong Kong would become a water-scarce city as a result of climate change in the future?

The chance is very low.

According to the Hong Kong Observatory, projections based on IPCC data suggest that there is a likelihood of increased rainfall in Hong Kong in the long term (refer to Question 1.2).

Calculations based on multiple climate change scenarios have also projected increased rainfall levels in Southern China.

3.3 When was the last time water was rationed in Hong Kong?

Water rationing was last imposed in Hong Kong in 1981. Since then, municipal water supply has never been interrupted.

Desalination

3.4 What is desalination?

Desalination makes use of the reverse osmosis technology to transform seawater into desalinated freshwater. Reverse osmosis refers to a process of applying pressure to seawater to push it through a semi-permeable membrance. Salt and impurities are removed, yielding freshwater as a product.

3.5 Does Hong Kong have a desalination plant?

The first stage of the Tseung Kwan O Desalination Plant was commissioned in December 2023.

The plant will go into full operational mode to produce freshwater when needed.

3.6 What is the capacity of Tseung Kwan O Desalination Plant in Hong Kong?

The first stage desalination plant can produce up to 50 mcm of fresh water each year.

As per a document presented to the Legislative Council by the Development Bureau, dated 2012, the proposed capacity of the desalination plant was determined to be 50 mcm. This figure was equivalent to 22% (upper bound) and 49% (lower bound) of the annual local yield for the period of 2001-2010.

3.7 How does the cost of desalinated water compared to those of other types of water supplies in Hong Kong?

According to data provided by WSD, the costs of water provision, on a per cubic meter basis at 2023 price level, were as follows:

Rainwater: HK$5

Dongjiang water: HK$11

Reclaimed water for non-potable use: HK$9.8 (March 2012 estimate)

Desalinated seawater: HK$13.5

Rainwater is the cheapest source of water. While the costs of Dongjiang water and reclaimed water are higher than rainwater, they are cheaper than desalinated water.

3.8 Is desalination a necessary option to augment freshwater supply in Hong Kong?

No, desalination is not a necessary option, based on an analysis of Hong Kong’s current water supply situation.

First, Hong Kong benefits from an abundant freshwater supply, sourced from the Dongjiang, at lower costs than desalination, even in drier years. In addition, Xijiang has become, since January 2024, a reliable backup source of freshwater for Hong Kong.

Moreover, while we should explore all possible solutions to capture sufficient freshwater to meet the needs of people now and in the future, we should also strive to reduce the adverse impacts of water use on the climate system.

Desalination, as a highly energy-intensive technology, would exacerbate climate change because it would generate much greenhouse gases emissions. The adoption of this technology should therefore be minimised as much as possible.

Hong Kong should, instead, formulate alternative, low cost, low carbon strategies to manage our water resources in a sustainable manner. The proven methods include water loss control, use of reclaimed water and water conservation, which can substantially lower the overall level of total demand for freshwater.